The New Iron Triangle: Achieving Adaptability and Scale in Defense Acquisition

United States Representative, First District of Virginia

Deputy Director, Strategy, Policy, and National Security Partnerships, Defense Innovation Unit

Principal Military Deputy to the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Acquisition, Logistics, and Technology

Senior Vice President, Army Programs, Palantir Technologies

Executive Vice President and President of Mission Technologies Division, HII

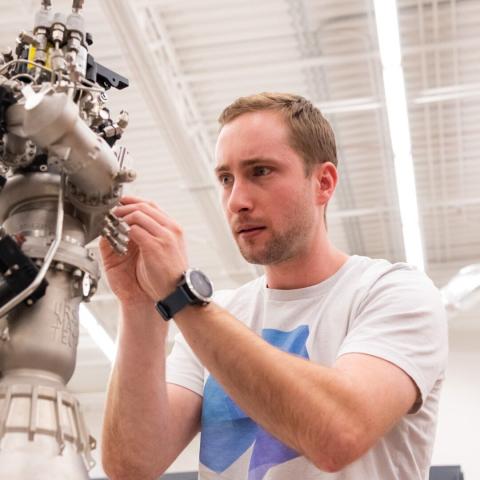

Chief Executive Officer, Ursa Major

Chief Strategy Officer, Saab

Chief Engineer, Epirus

Vice President for Government Relations, Varda Industries

Senior Fellow

Nadia Schadlow is a senior fellow at Hudson Institute and a co-chair of the Hamilton Commission on Securing America’s National Security Innovation Base.

Senior Fellow and Director, Center for Defense Concepts and Technology

Bryan Clark is a senior fellow at Hudson Institute. He is an expert in naval operations, electronic warfare, autonomous systems, military competitions, and wargaming.

This event is part of the Apex Conference Series.

The war in Ukraine offers numerous lessons regarding the future of military operations. One of the most important—and most underreported—is the value of adaptation. Ukrainian troops, previously on the offensive thanks to Western precision weapons, are now on the defensive as their rockets and bombs miss targets due to Russian electronic warfare. In the Black Sea, Ukraine’s early naval losses suggested Russian dominance. But lethal new naval drones have restored Ukraine’s access to the open ocean and constrained Russia’s fleet to its own coastline.

The United States and other North Atlantic Treaty Organization militaries will likely face a similar challenge in future confrontations against Russia, China, or their proxies. Merely stockpiling today’s weapons or expanding their production capacity could lock in obsolescence against technologically sophisticated sophisticated opponents. US and allied militaries will need an industrial base that can both modify today’s weapons or combat systems and produce them in volume—then be prepared to repeat the cycle in response to enemy countermeasures.

Join Hudson and the Apex Conference Series for a three-part event discussing the challenges and opportunities facing Western militaries and defense industries as they attempt to achieve relevant capability at scale.

Agenda

12:00 p.m. | Remarks and Fireside Chat

- Rob Wittman, United States Representative, First District of Virginia

Moderators

- Bryan Clark, Senior Fellow and Director, Center for Defense Concepts and Technology, Hudson Institute

- Dan Patt, Senior Fellow, Center for Defense Concepts and Technology, Hudson Institute

12:45 p.m. | Lunch

1:15 p.m. | Panel 1: The DoD’s Efforts to Achieve Relevant Capability at Scale

- Aditi Kumar, Deputy Director, Strategy, Policy, National Security Partnerships, Defense Innovation Unit

- Lt. Gen. Robert M. Collins, Principal Military Deputy to the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Acquisition, Logistics, and Technology

- Mitch Skiles, Senior Vice President, Army Programs, Palantir Technologies

- Andy Green, Executive Vice President and President of Mission Technologies Division, HII

Moderator

- Nadia Schadlow, Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute

2:15 p.m. | Panel 2: Industry’s Efforts to Develop New Approaches to Adapt and Scale

- Joe Laurenti, Chief Executive Officer, Ursa Major

- Michael Brasseur, Chief Strategy Officer, Saab

- Michael Hiatt, Chief Engineer, Epirus

- Josh Martin, Vice President for Government Relations, Varda Industries

Moderators

- Bryan Clark, Senior Fellow and Director, Center for Defense Concepts and Technology, Hudson Institute

- Dan Patt, Senior Fellow, Center for Defense Concepts and Technology, Hudson Institute

3:00 p.m. | Reception

Event Transcript

This transcription is automatically generated and edited lightly for accuracy. Please excuse any errors.

Bryan Clark:

All right, we’re going to go ahead and get started if everybody wants to grab a seat. Excellent. Well, thank you all for being here, and thank you to those online who are watching. Welcome to the Hudson Institute. I’m Bryan Clark. I’m a Senior Fellow here at the Hudson Institute. I’m Director of the Center for Defense Concepts and Technology here. We’re here to have an event today that we call The New Iron Triangle, looking at ways to expand adaptability and scale in the defense industrial base.

And to explain a little bit about the premise here. So program managers in the defense department often talk about an iron triangle of cost, schedule, and performance that govern how they go about building a new program, an airplane, a ship, whatever. What we’re finding today is that we’re experiencing a need for increased defense production. We’ve heard lots of arguments both here and abroad about how defense production is has kept up with the needs both to fight current wars like in Ukraine, but also to deter future wars such as in the Indo-Pacific.

But program managers are challenged to achieve that scale. At the same time, we’re seeing in places like Ukraine, the need to adapt. Ukraine received a lot of western equipment, Javelin missiles, JDAM bombs, HIMARS rockets that are now being countered by Russian GPS jamming and other electronic countermeasures.

So they’re having to adapt despite the fact that they got the highest end military equipment the west could provide. So adaptability and scale are now becoming the buzzwords or the watchwords for future defense acquisition. We can’t just adapt through innovation. We can’t just produce scale through enhanced production. We’ve got to somehow figure out a way to adapt and then scale the production of those things that we developed through adaptation.

So that’s we’re going to try and focus on today is this need for a combination of adaptability and scale and thus far that the DoD in particular has been challenged to achieve that we have a lot of great innovation efforts going on through places such as the Defense Innovation Unit, which we’ll talk a little bit about today with Aditi Kumar, and also on the services side so General Collins from the Army will talk about that.

And industry has been trying to support them, but those innovation efforts have not necessarily yielded the kind of scale we need to be able to prepare for a future fight potentially against China and to certainly support the current fight against Russia and Ukraine. So we need to come up with a way to innovate and then scale those things. There’s a need for new models of defense production. There’s new models for acquisition and we’ll talk about those over the course of today.

So thank you very much for being here for that. I also want to shout out our partners in this, the Clarion Defense, which puts on such great conferences like the DSEI Conference in London and in Japan. They’re partnering with us on this and they are putting on a conference next year called APEX in January of 2025.

And we’re working with them because one of the ideas behind APEX is this idea of achieving adaptability and scale. How can we produce other kinds of capabilities we need and then evolve them over time in response to a changing security environment? So thank you very much to them and we’ll hear a little bit more from them later on today.

But to start, our first discussion is going to be a panel discussion or rather a small panel discussion between me and Congressman Rob Wittman. Rob Wittman is a representative in the US House from the first district of Virginia. He is the Vice Chair of the House Armed Services Committee and the Chair of the Tac Air/Land Subcommittee, which has actually had the largest portfolio within the House Armed Services Committee. He’s also on the Natural Resources Committee where he does a lot of great work at protecting Chesapeake Bay and has been diligently working for a decade or more trying to improve the ability of the Defense Department to both produce at scale as well as adapt to a future environment.

So join me in welcoming Rob Wittman to the stage and we’re going to have a discussion.

Rob Wittman:

Thanks, Bryan. Appreciate it.

Bryan Clark:

Well, thank you very much, Congressman Wittman.

Rob Wittman:

Thanks, Bryan. Appreciate it. Thank you.

Bryan Clark:

Thank you for being here. So to start with, obviously it’s a very busy time. Over on the hill we’re doing final markups and approval of the Defense Authorization Act for 2025 and obviously a lot of other activity up there as well. Can you lay out for us where you see one, the challenges that we’re facing in the US military and our allied militaries, and then what some of the opportunities are to address those?

Rob Wittman:

Sure. Well, we’re in the process now. The Rules Committee has met, they’ve made their final determinations of the almost 1400 amendments that have been put in. There are 350 that have been accepted in what’s called In Order. Many of those will be on block. It looks like about 58 of those amendments will be debated. So we’ll go through that process today and tomorrow and then ultimately final passage vote on Friday.

So our desire is to make sure we get that passed. The last thing I want is for it to not pass and then us have to go through a suspension process. I think that sends a horrible message to not only our members of the military but also the nation.

And the challenge for us is to do several things. First of all is there is an issue with recruitment and retention. So there’s a lot of focus on this year’s NDAA with quality of life, and that includes raising the pay of our junior enlisted, making sure we’re taking care of families, understanding the nuts and bolts about what is necessary to make sure we retain those members of the military and what they do, but also create the incentive for us to recruit the best and brightest.

And you can’t do that by saying, “Well, the starting pay for a junior enlisted is $23,000 a year.” Which is $11 and 50 cents an hour, and we’re asking people to raise their right hand and swear to uphold and defend the constitution and put their lives on the line for $11 and 50 cents an hour. They look at it and go, “I can go down to Chick-fil-A and serve chicken sandwiches in heating and air conditioning and get healthcare benefits and make $16 an hour. Where’s the motivation there?” Now listen, many people have a greater sense of contributing, but that’s a big issue for us to be able to take care of.

The other is how do we modernize at the speed of relevance? And there’s been a lot of great concepts that have been projected by the service branches and by the Pentagon. Things like Replicator, things like how do we produce expendable systems, attritable systems? So the concepts are there and even some of the elements of RDT&E, research development, technology and engineering, and looking at how we bring those concepts to light.

But what’s lacking is the execution. And that’s been, unfortunately, the problem with the Pentagon through the years is great concepts, lots of talk, lots of back and forth and some great science experiments. But really the key is how do we get these things to scale quickly and how do we not let perfect be the enemy of the good? How do we make sure that we say “We’d rather have the 70 percent solution in the next 30 days than the 100 percent solution five years from now?”

And the problem is we have to overcome that paradigm. In closing with this, the Pentagon, since its very inception, has been a hardware-centric organization. Great at going through years of writing requirements and acquiring big exquisite platforms. And we’ve been used to living in a world where the exquisite platforms have been the overwhelming superiority that we’ve enjoyed. But if nothing else, we’ve seen what’s happened here in recent history, especially in Ukraine, and know that it will not be expendable platforms by themselves that allow us to make sure we counter the threats.

It will be how do we quickly and effectively feel expendable systems that can be literally tuned on a daily basis based on the nature of the threat. And then how do we produce attritable platforms? Because the most valuable asset in the United States military is not the hardware, it’s not really even the software, it’s our men and women in the military.

How do we find ways to put them in situations where they don’t have to be in harm’s way? I can think of many situations where there’s no need to put a human being out there to collect ISR. There’s no need to put a human being out there to do jamming and in some instances not even need a human being to go out there and launch weapons. Now they need to be in the loop. So the question is how do we do those things? And again, the Pentagon needs to go from a hardware-driven organization and now be software-driven. Software needs to inform everything that the Pentagon does. Anything in the hardware realm needs to be designed around what the software can do and then we’ll actually be able to operate the speed of relevance.

Bryan Clark:

Right? Absolutely. Those are excellent points, which we’ll dig into in the course of this conversation. So when I mentioned the idea of the Iron Triangle, the old Iron Triangle cost-schedule performance is all based on a set of requirements that came over from the operational community and they were treated like Moses tablets. We don’t change the requirement. We just work on trying to satisfy that need.

And obviously as you’re talking about with a 70 percent solution, it kind of implies a New Iron Triangle where the operator’s got to be part of that discussion. So the operational concept, the tactic is one corner of the triangle and then maybe relevant capability and relevant capacity are the other two, as those are the things you’ve got to meet as a program manager. You’ve got to have enough of them, they’ve got to be good enough and they have to satisfy an operational concept of the war fighter.

So for that new triangle, how do we get the operators to be more involved to be able to define what is that 70 percent solution?

Rob Wittman:

Bryan, that’s a great question. If you look historically when acquisition was done, you had the operator was in the same room as the requirements writer who was in the same room as the acquisition professional. So they all talked to each other and they knew basically what the platform was about, what was the challenge that the operator was facing so there was this conversation.

Today, the operator’s over here, the requirement writer’s over here, and they’re reading what they believe is the mission objective and they go, “Well, this is what I think it is.” And then in the acquisition professional’s over here reading the requirement and go, “Well, I think this is what they mean with the requirement.” So the operator says, “I need an apple.” And then the requirement writer writes it up and it’s really an orange. And then the acquisition professional gets it and goes, “We need to acquire a pineapple.”

And then the operator gets the pineapple and goes, “What the. . .? This isn’t what I asked for.” And then they look at it and go, “It’s not what we need. It’s not going to be operational.” So what do they end up doing? They’re very innovative. So they say, “Well, let’s take the pineapple, let’s cut the top off of it. Let’s cut the rind off of it and we can get it to somewhat look like an apple and maybe function like an apple.” That’s really where we are today.

You have to make sure you flatten that and you also have to make sure that time is of essence. You have to look at it and go, “As much as we strive to have these perfect systems, the world is operating at a very fast pace, especially as these threats morph and develop.” And as we see adversaries are pretty innovative. It used to be we looked at it and said, “We have the intellectual capacity here, the monetary capacity, all the requisites to make sure that we can predominate there.”

And we see today that those assumptions really aren’t as critical as timeliness is. And we see that folks that don’t have the amount of resources that we have or don’t necessarily have the massive amount of intellectual capacity can be pretty creative, can be pretty imaginative, and they come up with things quickly that can counter what we do.

Listen, there are lessons learned even prior to what’s happening there in Ukraine. There should be lots of lessons learned from what happened in Iraq and Afghanistan. We saw very rudimentary systems defeat massively expensive and complicated systems. And then we finally said, “Well, maybe we ought to go back to simplicity and speed and cost to be able to do that.”

So the New Iron Triangle really is going to be how do we create a system? How do we make sure to that timeliness is part of that? Cost is going to be part of it too. The competition today is not just with what China does, but the way we won the Cold War is we just out-resourced Russia. We had a bigger checkbook and Russia wasn’t interested in the economic side of things. China’s very different. China says, “We’re going to defeat you at every level. We’re going to go after you economically, we’re going to go after you strategically, we’re going to do things faster and better than you.” Because they start out with a blank sheet of paper.

When you go to the Pentagon and try to do acquisition, your paper starts out with a bunch of nos. “No, you can’t do this. No, you can’t do that. No, you can’t do this.” And you have to find pathways through that massive paper with a bunch of nos on it. So we have to find ways to be able to innovate and create.

So the new triangle needs to be timeliness. Not just cost, but how do we get value? How do we get more for our dollar than the Chinese get for their yuan? And then how do we make sure to that we change the paradigm that is based upon operational capability through execution. So execution has to be part of that New Iron Triangle.

Bryan Clark:

So you brought up software centricity, which is something we’ve talked about a lot here. The role that it plays in making for more adaptable force, and that’s not just both within the skin of an aircraft or a weapon, but it’s also between weapons and trying to create new force compositions that allow you to be effective even in a contest environment where an adversary is trying to defeat you.

So JADC-II or CJADC-II, the Joint All Domain Command and Control Initiative is the mechanism by which the DoD is trying to create this more recomposable force. Obviously it hasn’t gone swimmingly, they haven’t yielded a lot of output. So what do you see as some of the key elements though that could enable that more recomposable force? Obviously software is a part of it. Are there other elements there that we need to achieve the objective of JADC-II, even if it’s not accomplishing it?

Rob Wittman:

Well, listen, the concept of JADC-II is great, CJADC-II and we need that, but again, it’s an area where the concept is ahead of where we need to be to enable that. So you look at what we do right now to communicate lots of information, ISR information, targeting information, the system’s called Link 16. Now Link 16 is a pipe that’s about this and the amount of data that we need for JADC-II, and the coordination of all these systems, the pipe necessity is like this.

So the question is if you’re going to do CJADC-II, maybe you to build the pipe bigger first before you look at all this enabling software and things that need to be done. So first of all, we have to make sure that there’s bandwidth and duplicity there and bandwidth because you know the first thing our adversaries are going to do is to take down the ability for us to link those things. So how do we create layering there?

That’s why this year under the Constellation Security Program that Space Force has, which is called CASR, what we’re doing is we want to put that on steroids. We want to make sure that we have layering there. We want to get lots of LEO satellites, lower earth orbit, mid-earth orbit GEO satellites we want to get many of those in the private sector to have bandwidth reserved for the United States military. So that way we have layering and that way too, we have enough pipe to be able to move information around.

Second of all is how do you make sure that you have systems that can talk to each other? And that’s a key right now because a lot of legacy systems aren’t even designed anywhere close to, whether it’s the frequency itself or whether it’s how they exchange information. And I think too, what the Pentagon needs to do is they need to narrow the scope of what they want to try to accomplish initially with CJSC-II and CJADC-II, listen, they want to do all these things and it is great. Conceptually, it’s great. We want to coordinate, we want to make sure you can use different weapons systems, those kinds of things.

Let’s start here. Let’s start here. Let’s make sure we have a pipeline to just do a good job in gathering, targeting information, and then we can figure out how to get targeting information to different places. Let’s just make sure that it does a basic component, really good first. And if it does that, that’s the building block to say, “Okay, now let’s take the next step.” Instead of, again, the 100 percent solution that becomes very, very difficult and very difficult to achieve. Instead of saying, “Maybe let’s start with it being an excellent targeting data platform.” That’s how they need to go about it. So I think they need to draw in the scope of where they’re trying to go with CJADC-II.

Bryan Clark:

And it seems like they’re starting to do a little bit of that in terms of a bottom-up approach to building out different kill chains as opposed to trying to make the entire force recomposable and every shooter in every sensor can be working together instead say, “Well, which kill chains do we need to do first and building those up?”

Rob Wittman:

Exactly. And how do we make sure too, how do we understand the sensors? How do we modernize them? How do we get them to talk to the combat systems out there out there that can deploy that. The human being’s going to be in the loop there somewhere, so don’t expect too much performance out of it to begin with. Where it can really be a value is with all the sensors we have, all the data we have, how do you make sure you can synthetically annotate that data, put it in a form that’s targetable or targeting data and then get that to the war fighter? That would be a massive improvement just by itself.

Bryan Clark:

And I think people don’t. . . they lose sight of that because I think we think with all the sensing data that’s out there, all the kind of ubiquitous commercial sensing, you’d think, “Well, I can see everything on the surface of the water or the earth.” Which may be true, but that’s not target quality data.

Rob Wittman:

That’s right, exactly.

Bryan Clark:

The difference between those two things is enormous, and that ends up being a big roadblock to a lot of the operations that DoD wants to do or US military wants to do.

Rob Wittman:

And it’s essential with our kill web, especially as you look at where we are today with magazine depth, our magazine depth on long-range, precision weapons is horribly shallow. So you cannot afford to be firing any of those weapons without really high-grade targeting data. So what you don’t want to do is to go, “Well, this data is good enough,” because guess what? If you miss, then you create a double effect on what your challenge is on the next shot, and the next shot.

Bryan Clark:

And going back to the idea of adaptability and scale, what that highlights is if you’ve got better space-generated targeting data, that might give you a lot of flexibility in terms of what your weapons might look like and I employ weapons that maybe aren’t quite as sophisticated as maybe the preferred ones of today? And I can use unmanned vehicles that don’t necessarily have the autonomy that you’d want in a fully autonomous vehicle, but they can get the job done because they’ve got this great access to targeting data coming from outside.

Rob Wittman:

That’s it. Bryan, you talk about mass, when you have that ability to get that targeting data, all of a sudden mass and expendable platforms means something. And listen, the Chinese have looked at that and said, “Listen, we’re going to generate mass and capability.” Our challenge is to look at capability and capacity and say, “How do we generate that in mass?” Because that has an effect and it doesn’t have to be an exquisite platform.

I would argue the best way for us to generate mass is through expendables and attritables. I think the greatest opportunity for us as we look at challenges in the tactical aircraft space is CCAs. That to me is the gap closer that we can do quickly. I am excited that the Department of Defense has decided to award the initial contracts to two smaller companies, to innovative companies. So they’re getting away from the paradigm that everything has to be large-scale companies that. . .

Listen, I don’t want to in any way, shape or form criticize them. We need them, but we also need other smaller companies that are innovators and creators. So the second tranche of awards on CCAs, the remaining competitors will be part of that. So we need everybody to be involved in this. The gap closer there is how quickly and effectively can we do CCAs? I would argue that what they do to enable an F35 if we can ever get the improvements to F35 done, we’ve done significant things to close the gap.

Bryan Clark:

Right. So CCA, that’s a great point on that. And the fact that they’ve gone to two private companies that are putting a lot of their own money to work in that I think is an important point. Do you think that that’s a model we need to look at more going forward when we start to try to field more unmanned systems that are going to be 70 percent solutions? Are we going to depend on industry doing a lot of that legwork to develop that system, anticipate what the war fighter might consider to be good enough, as opposed to getting this into a long R&D cycle where the department’s managing this centrally, this idea of industry independently coming up with potential solutions?

Rob Wittman:

Listen. Bryan, there’s already an incredible amount of work that’s been done by these small companies out there and they have very, very innovative and creative ideas about how to do this, and they’ve actually fielded those systems and tested them. Why do we want to recreate the wheel? Why don’t we want to say, “Let’s compete with those companies that already have those platforms there.” And the Navy’s starting to do some of that with unmanned surface platforms. Let’s do that to scale. And if you’re going to do that, take some risk and say, “Listen, it’s not just one company, but maybe there’s a half a dozen companies out there that all do really good things. Let’s feel those systems. Let’s do it masse.”

Here are the two case examples that we ought to look at. When we saw the need for unmanned aerial systems, it was Congress that said, “Let’s do it.” And guess what? We did multiple company acquisition. When Congress said “We got to have something that protects members on the ground from IEDs in Iraq and Afghanistan.” We did acquisition on MRAPs. And instead of saying, “This one company does it.” Guess what? We had a half a dozen companies do it and they manufactured a thousand MRAPs in six months.

Same paradigm needs to be used for these unmanned systems. We’ve got a lot of great companies out there. Let’s take some risks. Let’s put a bunch of them out there and let’s figure out, “Well, this one works really well, this one not as much or maybe we can make a change to that one.” If we’re going to generate mass quickly, it cannot be with a single company because remember, a single company is also a single point of failure. So let’s take some risks, let’s feel those platforms. Let’s get a bunch of them out there. If we’re really going to expand the industrial base to have the capacity we need, you’ve got to be able to acquire expendables and attritables and even for that matter, exquisite platforms from multiple companies.

Bryan Clark:

Right. And so one of the challenges that comes up with that is transitioning those into use and actually fielding them and sustaining them. And we’re going to hear from DIU here in a little bit. And one of the challenges they have is they’re going to buy a bunch of systems under replicator, but then how do they get those in the hands of the operators somewhere out in the Indo-Pacific for example.

So how should the department be thinking about that challenge of fielding these systems? Especially when you think about fielding a joint system of systems, which you can’t just give it to the services because then it’s got to be brought back together by some poor operator in the field. Do we need to have a different construct for how do we get these systems out there in a joint unit to start with?

Rob Wittman:

I think what you need to do is you need to be able to engage the operator essentially at the unit level. So let’s take a soldier that’s operating at the squad, platoon and company level and say, “Okay, how do you and your mission objective for your unit, what are the things that you would need in a UAS?” And then let them with whatever platforms are out there, let them experiment with it.

And in general, George I think is this concept in mind to be able to do that, his transformational effort there to actually do it at a tactical level, and that’s great. And then you get a lot of feedback. So the operator tells you, “This is what we need, this is good, this is not so good. Let’s add those things in.” You have to be able to do that on a pretty fast pace and on a quick trajectory to be able to get that to the point where now you can feel that in mass.

And what we did in this year’s NDA and it got through is to create a drone corps in the Army. And listen, you’ll hear from the Army folks a little bit later on. Now listen, they’re resistant to that. They go, “Listen, we’re already doing that. It’s at the operational level. Our soldiers are going to develop this and we don’t want to this structure within the army, we think we can do it here.”

The problem is this is, I don’t disagree with the concept of saying “We have to develop these operational concepts and what needs to be in those platforms.” That needs to happen at the unit level. But the key is is that if it happens at the unit level and every unit’s going to have their own little idea about what needs to be in that UAS or that counter UAS system. So the question is then how do you acquire it in a timely way?

There needs to be some entity there that says, “Okay, we’re taking all this data in and we believe the best combination of that is to do this combination of things and we can get it out there and it can do. . .” Again, 80 percent of what the operators want it to do instead of starting with the apple and giving them a pineapple. That’s where I think things need to be. So what we want to do is to make sure that there is that level of what we call the drone core, where there’s a centralized effort to bring all this information in from the operators and go, “Okay, now we’re going to operationalize this. Now this is how we can bring this to scale quickly.”

And what I get concerned about is we’ve watched the service branches and all of them have done that through the years, and that is they do a great job in doing experimentation with a lot of things, but the challenge is to get across that valley to actually get it acquired.

And the example is SOCOMs figured this out. Special operators have said, “Hey, listen, we get it. We know what we want and we know how to acquire it.” Why? Because they come up with a paradigm that says, “We do fast acquisition. It’s part of who we are, it’s part of the nature.” And that’s how they operate. The question for us should become, why is that the exception? Why shouldn’t it be the rule? How do we design a system to where all of a sudden we do that just as a matter of fact and how we operate? So you have to be able to merge both of those.

So you have to have the drone core concept and still have the transformational activities that General George talks about that are bottom up, that are operator up. We can do that. We can do both. You can’t just say, “Oh no, we don’t want drone core. We’re going to do all this organically.” Because the concept sounds good, but operationalizing it in mass is always lacking.

And listen, I love the army. They do a great job, but they’ve also had a pretty challenging history with aviation acquisition. You go back to Comanche, you go back to all the things that they’ve tried. You look at FARA this year, discontinued FARA. Listen, by the way, I think that was the right thing to do. I wish they’d have done it a year earlier, but they are saying “We’re going to do UAS and counter UAS.” So there are good things happening there. The question is how do you integrate all of those things, both at the operational level and at the acquisition level?

Bryan Clark:

So it seems to argue for the idea that the program manager needs to be part of that discussion. So you can’t have the program manager off, “Well, tell me when you’re done and I’ll get to you.” They’ve got to be in the middle of this conversation between the operators and the industry people.

Rob Wittman:

They all have to be in the same room. Listen, the requirements writer needs to be there. In fact, I would argue in some instances, you don’t even need a requirement to be written. You need to make sure the acquisition person is there. So the acquisition person needs to be embedded at the unit level. So if you’re going to do that in timely ways, the acquisition person needs to be there. They need to be out in the field talking to the operators as they’re experimenting with these things. If you want to do things at the speed of relevance, that’s the way to do it.

Bryan Clark:

Right. And the SOCOM model was sort of based on the idea that, “Well, SOCOM’s worried about near-term problems.” And so the technology of today is all that matters to them and that the services are worried about the longer-term challenges that the DoD faces. But technology has probably changed that, right? So technology now means that I can both worry about today’s problem and evolve that to address tomorrow’s problem.

Rob Wittman:

Software centric and give me the 70 percent solution tomorrow. I don’t want the 100 percent solution a year from now.

Bryan Clark:

Right. And so you’re bringing up software, and I wanted to ask you about that. So the DoD is trying to do a better job of buying and paying for software through new software acquisition pathway, new software appropriation, but it seems like they’ve been slow to adopt it in any meaningful way.

How does the DoD need to be able to embrace the kinds of software-centric approaches that we’ve been advocating, that you’ve been advocating? Do we just need them to embrace these new models? Does it need a different relationship with industry, which might need to be continuously building systems or software for them?

Rob Wittman:

Well, I think you start there. You have to understand what are the capabilities that software can even bring to the tables. You have to understand the scope of what’s there, and then you have to be able to say, “Okay, now how do we write an acquisition strategy around that?” And that’s difficult because software tomorrow is different than what it is today, especially if you’re going to adapt and it’ll be different the day after.

So how do you create enough latitude in that contract where you allow the operator to talk to the acquisition person and then the customer can then go to the company that delivers the product, the software, and say, “This is how we want it to change.” That’s a very difficult paradigm. And where it’s also difficult too is that as authorizers get more and more of that in mind and what we see needs to be enabled through the military, listen, we get it. And we’re trying to push in that direction.

The challenge is is appropriators don’t like any flexibility. “We want to tell you how to spend the money.” And listen, I understand because they feel they’re responsible for doing that, and that’s part of their reach and part of their power. But also on the congressional side, this has to be a team play. This has to be the Pentagon, it has to be the executive branch. It has to be the legislative branch that say, “Okay, we’re going to give you some flexibility because we know what you’re acquiring is a very dynamic product.”

And listen the private sector does it all the time. A great example and Doug back there at DIU is the perfect way to be able to transcend this outside of DIU to the rest of the Pentagon, is Apple had a perfect strategy to be able to do that. Apple looked at it initially, Stephen Jobs said, “We’re going to make the iPhone and we’re going to do everything internally. We’re going to do it ourselves. We’re going to develop the software and the hardware.” And they figured out that there’s some really good stuff out there that they themselves didn’t develop.

And when they tried to solve these problems, a great example is when you dropped your iPhone and the screen cracked, they got all these returns because the screen cracked. They go, “Well, let’s come up with a glass that’s resistant to fracture.” And they found out that they could do all this experimentation, but there’re actually companies out there that are doing it now where they could acquire that much faster and much less expensively. So look at Apple’s model and what they do, they’re looking at it and go, “We’re not going to try to be the monopoly on every technology in our phone, but you know what we’re going to do? We’re going to find the best technology and we’re going to be the systems integrator and we’re going to integrate that into our phone. And the iPhone is still going to be the best phone out there.” Now listen, Samsung customers, Samsung thinks the same thing. So I’m not making a judgment on those phones, but that’s how those companies operate.

Doug gets it, and what Doug I think needs to be able to do from DIU is to expand that concept about how you take the best of what’s out there and actually integrate that into systems. The government, instead of being the acquisition central place that determines everything that says, “We have to make it, DOD has to make it. And if we don’t make it, then it’s not what we need and we’re going to drive all the requirements.” And instead of that, the government needs to say, “You know what? We need to do a better job in acquiring software and we need to be the systems integrator.” So we need to think, where’s the best software? And it may be a combination of software. Maybe this software does this really well, this does that very well. How do we combine those? How do we team some of those companies that do that? And then how do we team to the hardware that’s out there and how do we make sure the software enables the hardware?

If we do that and when we do that, that’s how we get to the place we need to be to operate at the pace of relevance. And that’s a tough place to go because the Pentagon is very structured, there’s a very static model about how they do acquisition. And it all begins with, again, that requirement writing. And I look at MTAs and OTAs, again, appropriators get really mad when you use OTAs because it’s like we don’t like to give all this flexibility in the acquisition. But OTAs and MTAs need to become more the practice than the exception. Changing the acquisition paradigm is necessary.

Bryan Clark:

So when you’re buying software, I think one of the things too is the idea that you might be able to have multiple companies competing to deliver the same software. Because one of the challenges that the appropriators are worried about is, “Well, once I get locked in with a software provider for this capability, I’m stuck with them forever. I’m not going to have this ability to pivot to another provider because somebody’s already so entrenched.” But if you could have multiple providers delivering the same kind of software-

Rob Wittman:

Yeah. They ought to encourage teaming. Listen, we do it for Virginia class and you bring the best of those two companies. Why don’t you say, “Hey, listen, we’re going to put an RFP out there and we’re going to score those based on the highest level of innovation and creation that you bring to the table. And if you want to partner with another company that does this well and you do this well, and another company does this well, we’re going to score that even higher.” So you’re going to encourage teaming. And then all of a sudden, how does innovation and creation happen? A number of different minds working on it. And this company may say, we got this viewpoint. And you combine that with another viewpoint, all of a sudden you go, “Wow, I didn’t even know that was possible.”

Bryan Clark:

Right. And you can recompete it so that you can say, “Well, we can change the teaming arrangements as you go.”

Rob Wittman:

Exactly.

Bryan Clark:

And so the last thing I want to bring up before we go to audience questions is this idea applying that model to other parts of the supply chain, if you will. So one of the obviously strengths of Apple is its supply chain understanding and strength of providers.

Rob Wittman:

Yes. Right.

Bryan Clark:

So for DOD, we tend to build very kind of narrow supply chains for each of our systems. Do program managers need to be given an incentive to basically create a more resilient supply chain, even if that might mean the system costs more, maybe the performance is going to be less than what optimally could be provided if you had the exquisite set of providers.

Rob Wittman:

Well, Bryan, I think the most fundamental thing that needs to happen is certainty, certainty in the acquisition realm. And Congress is at the very forefront of creating uncertainty. Why? Because every year we adopt CRs, there’s no way that you can stay on a known path if you do CRs every year. It wastes money. It doesn’t allow you to advance at the speed of relevance. So Congress needs to get its act together. So if you’re going to have those innovative and creative opportunities, there has to be certainty for folks.

Listen, people are willing to invest. There’s a ton of private equity and venture capital dollars on the sidelines there that said, “If you send us the demand signal, we are going to do that.” But you can’t be up and down. And then two, you have to make sure that there’s continuity in what happens. And a great example is this year in the Virginia class submarine program. We’re now in AUKUS and AUKUS is going to require United States sell some submarines to Australia. And we’ve already said we have to be producing on average 2.3 submarines a year, which means you really have to do on a cadence of three, two, three, two. So this year we came back in and the President’s budget comes over with one submarine and the Australians go, “What the. . .” And we said, “You’re right. We have to stay at least two.” And the industry is trying to recover from COVID, so they’re adding new people in the workforce, so they’re ramping up to be able to get to that too. And so we’re doing that, but then it looks like the appropriators are going to go back to funding one.

So how do you go to the Australians and say, “We’re serious about that.”? How do you make sure that the industry gets the demand signal and say, we are going to ramp up and hiring people and developing that skill set? And I don’t care what you say. Well, some of this will go to AP. Listen, there was $3 billion in the Taiwan supplemental to go to submarine industrial base. That is the necessary step to be able to build that portion of it. But the only way that you’re going to get to that production rate is you can’t say, “Well, we’re going to fund some AP and some ship sets and that’ll be the substitute for another boat.” No, it’s not.

I mean, these yards are not going to hire people on for the promise of another boat next year. And by the way, when you lose a year of building another boat, you’re never going to make that up. So even if you say, “We’re going to go back to two next year.” So the industry goes, “Well, now we got to bring people back,” and it’s not going to happen. We also have to send a constant demand signal and we have to stay on track. Because what happens now is that industry isn’t only trying to battle the uncertainty of a CR, but they’re also trying to battle the uncertainty of spotty acquisition strategies where the Navy says, “Let’s build two. We need 2.3, but let’s only go to one next year.”

And then it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. And the reason they say is, “Well, we don’t think the industry can do it.” Well, duh, if you don’t send the demand signal, the industry’s not going to do it. So if you send the demand signal, guess what, and demand that from the industry, I think the industry can perform. So again, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. So it sets my hair on fire when I hear the Navy say those things. But that’s where we need to be. And Congress needs to hold the Pentagon’s feet to the fire to say, “No, you are going to do this.” So we’re kind of working through with the appropriators how to make sure that happens.

Bryan Clark:

A component of that too is are you designing your program and are you managing your program in a way that tries to increase the number of suppliers that are possibly able to deliver components for your program, and are we willing to deliver the kind of money that is necessary to incentivize those suppliers to come on board and stay on board?

Rob Wittman:

Right.

Constant demand signal and making sure those suppliers can look out in their windshield five years, 10 years and go, “Yeah, I’m going to continue to do business there.” And not say, “Well, I’m going to have to manufacture one ship set. This ship is going to be out the door in two years. What happens after that? I don’t know.” So those companies most of the time say, “You know what? I’m not in that game. I’ll go somewhere else. Do something else.”

Bryan Clark:

So I want to open up to questions from the audience. So if you have a question, please raise your hand and Morgan will bring the microphone around to you. And if you can state your name and affiliation and keep it to a question, not a comment. Oh, and I’ll start with you, Vago Muradian.

Rob Wittman:

Yes.

Bryan Clark:

That wasn’t intended just for you.

Rob Wittman:

Vago.

Vago Muradian:

Vago Muradian with Defense & Aerospace Report. Terrific event, off to a great start. I have two questions, but they’re interlinked. Sir, great comments, US Air Force is looking at a more consolidated requirements approach to both be able to siphon up good ideas from the bottom, but also enforce discipline and figure out crossover as opposed to each of the individual branches of the Air Force doing this. Do you like that overall approach as maybe a model for the other services, given that nobody has a consolidated requirements? We’ve tried this with Futures Command, is that a template? And I have a follow-up.

Rob Wittman:

Listen, I do like that because it’s driving the idea of writing requirements or needs from the bottom up. So you use it at the operational level, you look at the tactical needs there, you bring that up. But then you have a unified strategy to say, how do we then acquire in a timely way in its scale and with value? And those are the three metrics that have to be done. And that’s why our idea about the Drone Corps in the Army is it can’t just be an operational idea of up flow. It has to also be, now how do you combine those? How do you synthesize all those things to do acquisition in time and in scale? And that has to happen.

Listen, the Air Force has got a pretty good record of doing that. You look at our Air Force RCO and B-21 acquisition and things that they did there, they were great at systems integration there, and they were embedded with Northrop as Northrop started. And listen, when I chaired CPOWER, I was somewhat skeptical. I went out to Palmdale there with Northrop, with Air Force RCO, and I said, I don’t know if you guys can pull this off. They were just hiring engineers there. And I thought, this is a big enterprise, most advanced aircraft ever in the world. Can you pull this off? And to their credit, their credit, because they were embedded with Northrop, everything that happened happened at the speed of relevance, all of a sudden they were able to do this, and then acquisition followed what they knew operationally would work.

So Air Force I think is trying to copy that paradigm is to make sure that now they can scale that. So I think that’s the way to go, is how do you get the operational level impact? How do you make that scalable? How do you make sure too then that becomes how the service branch operates. And again, it’s value, it’s timeliness and it’s innovation.

Vago Muradian:

The follow-up I was going to ask was about the cyber corp. There is a sense, for example, I mean, had the Army been using air assets, no criticism of the Army, we wouldn’t have created an independent air force to be able to use air assets differently as opposed to tying them to units. Now we’re saying, okay, there’s a recognition of these unmanned assets. But we are looking at individual purposed organizations, whether it’s a drone corp, whether it’s space force, what are your thinking on whether or not we need a cyber corp? Because cyber is more granular and interspread through each of the fabric of the services and indeed conjoined increasingly with electronic warfare through General Schmidle’s innovations. What’s your sense on whether we need a cyber corp or better integration actually across the fabric of the force? Thank you very much.

Rob Wittman:

Well Vago, that’s a great point because where we are right now is we have really changed. It used to be the service branches everybody had their own hardware, their own software, even using floppy disks in the day. And now what’s happening is everybody’s going to the cloud. And listen, the cloud is a great asset, but to think that somehow there’s no threats within the cloud is also pretty myopic. And the key is if everybody’s operating in the cloud and we know how that platform operates, are there commonalities that we can put forward to say, how do we protect that exchange of data? How do we protect what we do in the cloud? How do we make sure that cyber protection is there?

So yes, there is application to do a Pentagon-wide effort to look at how do we put those basic protections in? And I would argue the way the military operates today, which used to be in buckets, this was your operating platform, this was your way that you used and kept data is very different than today. We do data on the cloud.

And then another thing too is that how we are changing today is as data started out in being converted to a usable form, it was human annotation. So you take a bunch of photographs of intelligence that you’d gather and you say, “Well, this is a Yuan class destroyer China.” And so you’d have to put all those together. So human beings would’ve to look at that. Where we are today is being able to use synthetic data annotation, but the question then becomes is then how do you protect that? There are all kinds of aspects of what we do digitally that if you don’t protect that and somehow that gets corrupt, and your adversaries say, “I don’t even have to build new ships. All I have to do is to trick the system to think that this is a Chinese ship that has capability.”

So there is a place. . . And that goes across all the aspects because every service branch will be using that data that comes out of that. So how do we make sure we do those things? And we have to be able to think in front of where the threats would go. And I would argue too that the cyber realm is not just an effort in what we do on the defense side, but we have to be more thoughtful, and I would argue more aggressive on what we do with offensive capability. And I know that we have it, most of it’s classified, but the question is how do we make sure that that is an integral part of what we do and how do we make sure too that we are more thoughtful about how we could apply that? And I would argue that is a strategic asset, and it is in many instances, much more effective than a kinetic effort.

And if we do that in a smart way and understand what the threats are, we can get out in front of the threats. And you talk about deterrence, if you want the biggest deterrence for how our adversaries are developing capability, offensive cyber capability is right there. So I think that has to go into how do you do that in a uniform sense? Because all the service branches are going to experience the same sorts of threats and the same capability that they need to build.

Bryan Clark:

And that’s doing a project for DOD right now on the non-kinetic capability supply chain, basically how do those capabilities get provided to the war fighter. Which there’s a lot of improvement that could be achieved there in terms of getting scale and adaptability in terms of what we can afford there. But yeah, that’s where a lot of the fight’s going to happen, especially if you look at dissuading a fight rather than fighting the fight.

Rob Wittman:

It is going to be in that realm, and I would argue major conflicts could be avoided if we get that right.

Bryan Clark:

Other questions? Yes. Yes. Right there.

Michael Hiatt:

Hi, Mike Hiatt from Epirus.

Rob Wittman:

Hi Mike.

Michael Hiatt:

Question for you on adaptive acquisition framework. Do you feel that that is doing the job of getting that timeliness that you’re talking about? And do you think, are there more ways that we can help smaller companies sort of bridge that infamous valley of death to get through that so that private equity money sitting on the sidelines see that it’s possible? Thank you.

Rob Wittman:

Well, listen, the adaptive process I think has started, but it is not happening fast enough. And what I want to make sure is that those small companies out there that don’t even know that they might have a product that is a great solution to the challenges that we face, how do they make sure that they can at least see into what the Pentagon needs? And we’ve been advocating for years that the Pentagon needs to have a windshield for those folks that aren’t intensely familiar with the acquisition process there. To where somebody can put up whatever their product is, software, hardware and say, “Hey, this is what we have,” and have some place there where the military can say, “Well, listen, we have these situations where maybe this could be applied.” And to have sort of a trial place where someone can says, “Well, this is what it can do,” to be able to search out and understand what are the possibilities out there right now.

It’s a go to the mountains. So they’re expecting people to come to the mountain instead of the mountain going to the people there. DIU is trying to say, let’s be the search component. Listen, and Doug and his group do a great job. They’re searching every day to try to find those innovators and creators. And listen, they spread a pretty big net to try to bring those in, but they can’t cover everybody and they can’t really be out there in front of what’s developing at the speed of relevance. So I think we have to have those things in addition to DIU in being able to discover where is this capability and capacity today and where may it even be at a developmental stage to say, “Well, maybe we need to get out in front and really understand what’s going on with that.”

So I think that those are things that we can do, and the acquisition strategy needs to be multifold, it can’t just be DIU or even OSC with Jason Maranci. It has to be how do we create a windshield in the Pentagon for somebody to say, “Well, I think I’ve got a solution. Let me try it.”

Bryan Clark:

Thanks. So do we have one time for one more question Hallie, or do we have to go? Oh, okay. Well then we definitely should let you go.

Rob Wittman:

Yes, thank you.

Bryan Clark:

We’ll leave it there. But join me in thanking Congressman Rob Wittman for being with us today.

Rob Wittman:

Thank you folks. Thank you. Thanks, Bryan. Thank you so much. Thanks for the opportunities.

Bryan Clark:

Thank you very much. So for everybody else here, we’re going to be taking a break until 1:15, so everybody can go get lunch and bring it back in here. We can get started at 1:15. We’ll have a panel with Aditi Kumar from Defense Innovation Unit, General Collins, assistant secretary of the Army for Acquisition and Logistics and technology, as well as Andy Green from HII and Mitch Skiles from Palantir in conversation with our own Nadia Schadlow. So we’ll see you all at 1:15. Thank you.

Rob Wittman:

Thanks.

Nadia Schadlow:

Thanks for taking time out of your busy day to be here, we really appreciate that and appreciate everyone in the audience as well. I thought I would start with General Collins and overall ask a few questions. We’ll try to have a conversation and then I’ll turn to the audience for the last 15 minutes or so for questions.

So General Collins, tell us a little bit about what the DOD is doing vis-a-vis Ukraine, Ukraine is an example that keeps coming up today but clearly it’s one of the most important ones in terms of the subject of today, modularity, adaptability, the ability to produce at scale, and what are we learning from Ukraine in terms of also addressing some of these problems of adaptability and scale?

Lt. Gen. Robert M. Collins:

Yeah, great question. And first, thanks for hosting this forum, allow us to have this dialogue and being up here with these participants. And I think it’s a great question. I think the strategic importance, certainly with Ukraine, I think obviously it has also allowed us in the department specifically in the Army to learn a number of lessons. We’ve got a number of modernization focuses. I’d say two that come to mind that have allowed us to really hone in on the munitions of fires and also when you think about defensive posture, air defense, those are probably two areas in particular.

When it comes to, part of the theme I think, is doing things at scale, producing velocity, doing things quickly. There’s the saying that production at scale is also a form of deterrence in itself. And so I certainly think that we’ve learned from a number of these areas that whether it’s government, munitions facilities, the defense industrial, there are probably some areas where we need to look at things that we can become more sophisticated and move into the digital age. Probably heard a lot, Javelin, Stinger, our guided multiple launch rocket system, Patriot. I’d probably hone in maybe a little bit on some 155 artillery, it’s probably been one particular area. Probably about a year ago. I wasn’t necessarily an expert on how to assemble a 155 artillery round. There’s a lot of things that go into it from the projectile to the casings to the energetics and all the raw material.

And I think that what we’ve learned is that there is a degree of sophistication that we need to look at and how we can move faster at scale, more multifunctional. I’ll specifically comment down in Mesquite, Texas, some of you may have seen the article down there. We just opened up a universal artillery production line. And one of those things does is it adds in things like autonomous vehicles to be able to move steel, robotic arms to be able to do things for the safety of folks that used to have to touch labor. When you start doing the forming of a projectile using software to be able to tune. So things like that allow us to move more quickly. And then I’d also say gives us a little bit of flexibility so that we don’t necessarily have to do one type of munition. We’ve got some versatility at how we do that. So those are some areas that I think that this has allowed us to learn and to be able to invest in our industrial base so that we’re ready to do things at scale.

Nadia Schadlow:

Was that factory stood up relatively quickly? It seems like it was. And a theme of this morning very much in the previous conversation was time, right? So it seems like that’s a big, actually, that’s a positive point in terms of DOD acting quickly.

Lt. Gen. Robert M. Collins:

I think one of the things that we’ve learned with Ukraine, and we’ve kind of put ourselves, I would say on a war footing, that we’ve been able to learn things not only about requirements, but acquisition contracting. We’ve been given some very special authorities to be able to move quickly, but that one in particular with the help of Congress, some of the supplemental dollars, we were able to take that facility to bring that capability and stand that up. In fact, we were all just down in Mesquite, Texas about two weeks ago, and they’re going through their first article testing. So that ramp and we’re route to a tenfold increase in our 155 artillery of what we had been producing about a year or two ago. So I think as you look at the speed of what we’ve done in past, I would put that as moving very rapidly.

Nadia Schadlow:

Amazing. Aditi, I’d like to ask a little bit about what DIU is doing in terms of allies and partners. We spoke about that a little bit offline and you were describing some interesting things to me.

Aditi Kumar:

Yes, thank you. And one point, just to extend what Lieutenant General Collins was just saying, we have done a lot of work with Ukraine and in that space on autonomous systems as well, in addition to traditional munitions, which you talked about. A lot of lessons learned on uncrewed systems and the use of those systems by both parties. And I believe the last time that I had the privilege to be here, I had just come back from Warsaw, Poland where we hosted a UAS conference with Ukrainian warfighters telling us what lessons they were learning on the battlefield. And the primary lesson was that we need to be able to not only upgrade the hardware, but definitely upgrade the software on those systems and that cycle that they described, which was shocking to me at the time, was every 90 days. Every 90 days is when we need refreshes.

And so actually just last week, the team was back in Poland in Kraków this time, and we were doing the second iteration of that UAS conference. And in addition to of course, dialogues, which are many very, very meaningful, we actually did a hackathon focused on, okay, how could you deploy something like this to the systems that we have in theater? And we actually had companies working with us to do, for example, last mile navigation for FPV drones that we can then use to integrate into the hardware solutions. And so these are all lessons learned about hardware, software integration and modularity that we have definitely picked up from Ukraine and in partnership with the Army and the other services are now incorporating into how we view autonomous systems going forward.

And of course, in addition to Ukraine, DIU in its current growth stage is focused a lot on deepening relationships with allies and partners more broadly and becoming the Department’s liaison when it comes to commercial tech adoption not just at home, but with our allies and partners. And that is taken on a few flavors, and we’re really executing that by embedding our folks in the DIU equivalents of our closest allies and partners. And so we have very strong partnerships, for example, with AUKUS nations, with India, Japan, Singapore, others, where we are working towards personnel exchanges so that we can really share information in real time, putting in place challenges where two nations together put out a requirement for something that both of us, or in the case of AUKUS, all three of us, have a need for.

We just did a challenge with AUKUS partners focused on electronic warfare, all three nations put out the same statement. We on the US side had about 50 companies apply, we’re in the down select process. And we’re starting to build those bridges internationally when it comes to commercial tech sector and creating sort of those ecosystems of founders, funders getting to know each other and us working across borders.

Nadia Schadlow:

So in a way, you’re setting a foundation for the systems integration across with allies and partners similar to what Bryan and Representative Wittman were talking about earlier.

Aditi Kumar:

Yeah.

Nadia Schadlow:

On one hand, it could be very complex, though. You could be adding complexity. We’re having our own problems within the DOD, but.

Aditi Kumar:

I think there is a broad recognition that we need to leverage the collective industrial base to tackle these problems. And so there is a lot of work to do in creating the international agreements to be able to do that, but we’re paving the way so that we develop the familiarity with our tech ecosystems, as I said, and we work towards these contracting opportunities that really materialize and scale across borders.

Nadia Schadlow:

And so speaking of AUKUS, General Collins, and then I’ll turn to Andy and then Mitch.

Lt. Gen. Robert M. Collins:

Well, I would just underscore we will always fight as a coalition or with allies and partners, one. Two, the more that we can share technically interoperability, training, all those procedural type things make us a more effective force. I think too, there are things that we can share. We’ve looked at co-production agreements. As you start to look at the luxury of a contested logistical environment, you can’t always, getting things to the point it need or having those things that are in place. Certainly when you start looking at particular types of regions.

I’d also say too, as we look at things for foreign military sales, it offers us an opportunity as you start looking at production and scale, as we ramp up some of these production lines, the more that we can have and other partners that are looking at US capabilities, I think those are things that can help us even from our industrial perspective. And so I think there’s a number of opportunities that we’ve learned with Ukraine and a whole host of other things that we can do across the FMS arena, and then taking early looks at what are those things from an exportability area that we just need to take into consideration and making sure that we’re doing our due diligence. And so it’s just kind of getting after that. And I think we’ve certainly seen increases in our foreign military sales over the last 12 to 24 months. So I think it’s a great point.

Nadia Schadlow:

And Andy, you’re right in the middle of FMS and Australia.

Andy Green:

Yes. By nature, Huntington Eagles is in the middle of AUKUS. But when you think about Pillar 1, that’s one thing with the submarines and the infrastructure and so forth. But when you think about Pillar 2, that’s when a lot of Aditi and General Collins, what y’all were talking about, we’ve got to smooth the pathway for technology transfer and do it in an orderly way, but we’ve got to be able to do it in an expedited way. So every last change or discussion or whatever, it doesn’t take six or seven months of an approval process. So I think y’all hit it right on the head.

I’m glad you brought up a contested logistics because it kind of extends into that contested logistics environment where you’ve got to have that ability to share information with our coalition partners very quickly and safely and securely, and that will kind of build off of these relationships that we’re creating through AUKUS.

Nadia Schadlow:

How is that linked to adaptability and modularity and scale? How are some of our partners thinking about that and how are you thinking about it as you AUKUS? And then, Mitch, I’ll ask you to comment on the software side.

Andy Green:

Well, we’re thinking about it in terms of adaptability and modularity kind of go hand in hand. And when you think about some of our coalition partners, they have the same challenges that we have. They’re kind of burdened by the old style as Mr. Wittman and as Bryan said, the old way of acquiring big platforms over a very long term. So we’re going to have to be more flexible, they’re going to have to be more flexible, and we’re going to have to be able to do that together and in sync and very quickly in theater. And so I think when you think about modularity and adaptability, I think that designing programs and designing platforms that facilitate that, and we’ll talk about it here in a little bit, Aditi and I talked about it. The Lionfish program is a great example of the type of program that is good for the US. It’s very modular, very adaptable, and would be just a fantastic program to also get our partners engaged in.

Nadia Schadlow:

Okay. Want to give Mitch a chance to jump in, but then maybe we can go back and you can tell the audience a little bit more about Lionfish. So Mitch, from the software side of things.

Mitch Skiles:

Yeah, I mean we’ve had the unique privilege of sitting at the nexus of where General Collins and his team are really increasing the production capacity on the, we think of hardware platforms and energetic side and then what Aditi touched on as far as actually delivering that capability to allies and partners and even our own forces that are supporting around the world. There’s this question when it comes to production capacity as a mechanism for deterrence, I’d certainly agree with that, but then ultimately, I think what drives the deterrence piece of that is what are we using that production capacity for and now can we actually demonstrate that we’re exploiting that to the maximum extent possible?

And that’s really right now what we’re finding and conflict in Ukraine has been an example of this, even comment on some recent examples in the Sankham region as well, where we can actually use software to go and understand the full availability of capacity, whether that’s 155 rounds or the particular types of effectors that we have distributed. All of the intelligence information that we have available to us and all of the objectives that commanders have, we can bring all that information together and then actually start to, whether through processes of automation or applications of AI or other types of capabilities, we can actually improve at dramatic rates the ability for the units downrange and our partners to actually go and deliver the effects on the battlefield that actually exploit that capacity to the point where I think our software and the partnership is actually driving the demands that General Collins was commenting on.

And it’s through that kind of full visibility in the supply chain and then actually seeing the results on the field where we’re delivering effects downrange at anywhere from 10 to a hundred times faster and more voluminous than has ever happened before, is really driving a level of fear and really effectiveness in the context of these partners that hasn’t been seen before. I think it’s starting to actually change an understanding of what software can actually do in terms of really bending the curve on I think the American deterrence priorities writ large.

Nadia Schadlow:

And it sounds like you’re working well with DoD. DoD is enabling or at least not creating obstacles to the speed of adaptation that you need. Has that been worked out over the past few years?

Mitch Skiles:

Yeah, I think something that we’ve seen change probably in the last decade or so is this recognition by the department. I think the Army led the way on this and now we’ve started to see this adopted more broadly. DIU, I think is a shining example of goodness right now where there’s this idea recognition that commercial companies and particularly commercial companies in the technology sector can and are innovating through their own capital and developing capabilities that can be utilized inside the department. And so historically the way this would’ve typically worked is you’d take RDT&E funding and then you’d identify problems inside the department. You’d use groups like DARPA or in the Army, groups like DEVCOM to actually go and start to develop new capabilities against those requirements, mature those, and then try to transition them over into larger programs, programs of record and get them downrange.

And what we found over the last 10 years or so is a great acceptance by the acquisition community to go and say, Hey, we can actually just buy capability directly from commercial industry and the amount of time, energy, costs to modify that into actually facilitating outcomes for DoD actually is a significant advantage to the department. And I think that realization by the department and then us working in close partnership to actually get some early results on that has really started to pave the way, not only for Palantir, but I think new entrants across the board. Anduril being, I think a great example of a quick follower in that. And now you have hundreds of startups emerging right now and tons of venture capital being poured into companies that can follow suit.

Nadia Schadlow:

So you sort of opened the door for my next question to Aditi about DIU pushing the department as a whole toward a more modular adaptable industrial base. And Lionfish is one example. Maybe you and Andy could talk about that a little bit, but could you comment on that in general also?

Aditi Kumar:

Yeah, I mean more generally I think there is a broad recognition that we need to move towards this space, and my boss is going to love that I use this analogy, but it would be like Apple putting out an iPhone and saying only Apple can develop all the apps. We don’t get the best product that way, nor does it make good business sense for Apple to do that. And so we need to bring that sort of model to defense capabilities and create the incentives for some of these primes to see themselves as platform providers that are then open for other firms to provide the best of breed, software, subcomponents, et cetera. And in some cases the prime may be the best place to provide those pieces just like Apple in some cases is best place to provide the app, but that doesn’t need to be the case. And so we’re really pushing that model because I think it makes sense for the warfighter, it makes sense for the taxpayer and it should make sense for the industrial base too.

Lionfish is a great example of that where we’ve partnered with HII. It’s an undersea vehicle with countermine measure capabilities and it has an open architecture as Andy mentioned, and one project that DIU undertook called Project AMMO is to again enable faster, more rapid software integration into this capability. And so it used to be six to 12 months and not floppy disks, but certainly hardware was involved in updating the software. It felt very archaic and through this Project AMMO, we’re able to develop an ecosystem and a pipeline and we have tested vendors updating the software in a matter of days. It’s 97 percent decrease in the time that it took.

So Lionfish is one example and Andy can extend that. There are others. We just announced the enterprise test vehicle that we’re doing with the Air Force, which again is a modular open architecture system. The vehicle is designed to test various subcomponents, so inherently needs to be open and it’s another great example of us pushing that capability forward and driving towards lower costs open capabilities.

Nadia Schadlow:

Andy?

Andy Green:

So just to add to what Aditi said about Lionfish, one of the things that I think made that program maybe not completely unique, but I think special and a special success, an example of success, is how it took, you had essentially the end user, the operator, you had DIU, you had NIWC Pac and you had us as industry all working together so that the customer was involved every step of the way, like we were talking about earlier with Bryan and Mr. Wittman, but the customer was involved every step of the way. DIU was involved every step of the way. We were constantly inserting new technologies.

Now, it started out broader and then they kind of down selected as they went through and then ended up, this happened over a handful of years and ended up in a situation where you now have this product and we’re talking about a UUV that’s about six, seven feet long depending on the configuration that two people can carry around. So very, very portable, very modular. We ended up with this UUV that the customer really, really liked, that our coalition partners really like and they really want because they want to be interoperable with the US and they like the modularity.

This particular UUV, I won’t go into technical details of it, but it was designed to be very modular so you could put whatever sensors you want on it, whatever payloads you want on it. Something in the Black Sea could be configured very, very differently from something out in the western Pacific and you could put on whatever, take commercial off-the-shelf sensors and put those on there, whatever you want to do. So there’s a lot of flexibility built into that. I think it’s just a great example. It’s small, it’s not a huge program, but I think it’s a great example of how DIU, the government, industry, the customer can all work together to really very quickly hone in on a good solution.

Nadia Schadlow:

General Collins, can you comment a little bit or build on that in terms of how the army has been thinking about open architecture systems and modularity and is there resistance to what Aditi and Andy have been talking about?

Lt. Gen. Robert M. Collins: