The recent BRICS+ summit in Kazan, Russia — featuring Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa — had some observers hailing it as the dawn of an anti-Western world order, led by Moscow and Beijing.

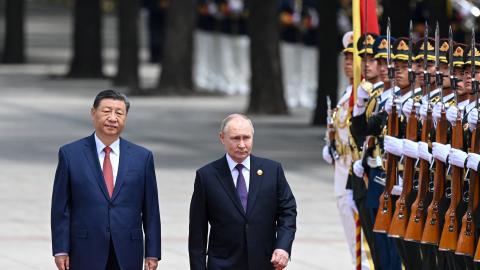

The partnership between Russia and China is undeniably formidable. Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese leader Xi Jinping have met over 40 times since 2012, with Xi meeting Putin more than twice as often than any other world leader.

Their shared disdain for Western power drives frequent joint military exercises, such as Vostok 2022, which showcase their integrated command structures and tactical coordination. Military technology transfers have reached unprecedented levels, with China gaining access to advanced Russian aerospace technologies and supplying critical semiconductor components for Russian weapons systems.

Yet this burgeoning bromance is likely more a marriage of convenience born of mutual opposition to Western power than a genuine strategic partnership guided by a common vision for the future. Beneath the facade of unity lie historical grievances and competing interests that could fracture the relationship once Putin and Xi leave the stage.

Tensions between Russia and China date back to the 19th century when territorial treaties, seen as unequal by Beijing, forced the Qing Dynasty to cede vast swathes of land to Tsarist Russia. The 1858 Treaty of Aigun and the 1860 Convention of Peking alone surrendered over 900,000 square kilometers (350,000 square miles) — an area comparable to the combined territories of Texas and France. Another 150,000 square miles were lost under the 1864 Treaty of Tarbagatai.

These agreements remain a sore spot for Chinese leaders, who view them as a legacy of exploitation during China’s period of weakness. The strategic significance of these territories cannot be overstated. Vladivostok, once Haishenwai, is now Russia’s largest Pacific port and home to its Pacific Fleet. The territories beyond Vladivostok also boasts timber, gold, rare earth elements, and significant oil and natural gas reserves in the Sea of Okhotsk.

Meanwhile, Russia’s Far Eastern population has been declining since the Soviet Union’s collapse, creating economic opportunities increasingly filled by Chinese businesses and workers from China’s populous northern provinces.

China has a well-documented strategy for reclaiming lost territories. Beijing’s incorporation of Tibet in 1950, its territorial reclamation and increasing belligerence with the so-called “nine-dash line,” and the ongoing pressure it places on Taiwan demonstrate China’s patient but relentless approach to territorial reunification.

It incorporates economic footholds, builds military infrastructure, and steadily asserts dominance over contested areas. This method is evident in its actions in the South China Sea, where Beijing first established economic outposts, then constructed military installations despite international objections.

Similarly, Beijing has pursued territorial claims against India in the Himalayas, clashing with Indian forces in 2020 and 2021. In Vietnam, China’s 1979 invasion and subsequent skirmishes over disputed territory and other factors demonstrate its readiness to use force to assert historic claims.

The 1969 Sino-Soviet border conflict offers a stark warning of how quickly territorial disputes can escalate and further illustrates that relations between the Dragon and the Bear haven’t always been so cozy. Fighting at Zhenbao (Damansky) Island on the Ussuri River led to hundreds of casualties and reportedly brought both nations to the brink of nuclear war.

The Donald Trump administration warned Moscow repeatedly about the risks of growing too close to Beijing. In fall 2020, Ambassador Robert O’Brien and Matthew Pottinger delivered a message to Russia’s national security advisor in Geneva: China’s historic territorial claims, combined with Russia’s demographic vulnerabilities, could eventually turn their partnership into a liability.Our counterparts clearly understood.

The advice was clear: every intelligence assessment, military exercise, and economic agreement the Kremlin undertakes should be viewed through the lens of China’s demonstrated pattern of territorial reclamation. Once the strategic partnership, bound together largely by the personal rapport between Xi and Putin, vanishes, Russia may be in for a rude awakening.

Enjoyed this article? Subscribe to Hudson’s newsletters to stay up to date with our latest content.